Dan Bronson

Some years ago, I wrote a little television film about an upscale community in which a shocking murder took place. It was my modest attempt to reinvent Dreiser’s An American Tragedy for our time. After it aired, I received a long, thoughtful letter about it from Keith. He totally “got” what I was attempting to do and offered insightful comments about the shallow, materialistic, class-conscious, status-seeking community and the destructive effects of its values upon its progeny—the fathers and mothers visiting their sins upon their sons and daughters.

But what he loved most of all was my high school principal’s speech at the opening assembly of the fall semester. Keith loved it because, out of the context of the film, it gave voice to one of his deepest convictions…

PRINCIPAL

It is excellence—excellence in the classroom, excellence on the playing field, excellence in the community—that distinguishes Santa Mira from its rivals. So, today, the first day of the rest of your lives, I issue this challenge to each and every one of you: I challenge you to be the best. The best son or daughter. The best student. The best athlete. The best individual it is in you to be. We live in a competitive world, a world in which second best simply isn’t good enough. And so, I ask you, what is your goal this year at Santa Mira High?

CROWD

TO BE THE BEST!

PRINCIPAL

AGAIN.

CROWD

TO BE THE BEST!

It could have been Keith himself speaking. He challenged his students …and everyone else around him…to be exactly that—the best! It was, of course, this passionate conviction, along with the C’s he awarded the students who failed to pick up the gauntlet he threw down before them, that led to his nickname, Captain Hook. Keith lived by his own words. He was the best teacher, the best husband, the best father, the best friend any of us could hope to have. How did he do it? By being the best listener I’ve ever had the privilege of knowing.

Not long ago, I had lunch with a bunch of friends from my days in the Paramount Story Department. One of our number started telling a story of how difficult it was for him to get into the Story Analyst’s Guild. Almost before he finished, another jumped in with her story of how it was ever harder for her. And the instant she finished, I assumed center stage with my tale of how it was still harder for me. None of us was really listening to the others. The only voice we were genuinely interested in hearing was our own. And this, I suspect, is true of most of us—probably everyone here today has, at one time or another, been guilty of exactly this kind of behavior.

Keith was not. Keith was different. He listened…and he heard. He listened and he heard because he was genuinely interested in everyone and everything around him. It was this quality that made him such an extraordinary teacher, husband, father and friend. He listened to me, I know, with such attention and interest that I’m convinced he was one of the few people on the face of this earth who wholly understood me. I’d be very surprised if most of you here this afternoon did not feel exactly the same way.

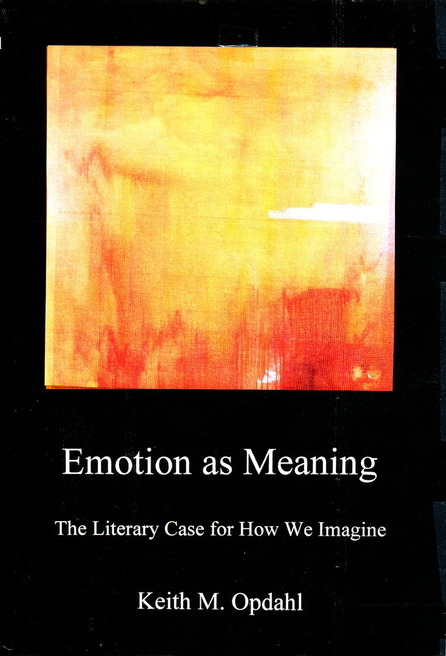

If Keith was interested in everyone and everything around him, he was also amused, responding with gentle, sometimes critical, sometimes affectionate laughter to his government, his society, his colleagues, his friends, and most of all himself. He wrote a wonderful, semi-autobiographical novel in which all these qualities shine through, and I’d like to share a brief passage from it with you…

"She had married a glamorous young professor (never mind that I was a teaching assistant) and had awakened in bed with a Norwegian peasant …I might have looked like a typical American, but I had an unnatural need for smoked fish…As my wife, Sarah had become ‘Mrs. Olaf Solomon Olsson, Jr.,’ confirming the tragic truth: she had married the kind of fellow who wears a hat with ear flaps."

Self-deprecating, modest, amused and amusing. That was Keith. But what you hear in this passage and in every aspect of his life is warm, gentle laughter at a world that he found endlessly fascinating.

Perhaps my favorite of all the characters I created in a long career as a writer was an old man named Will Clare. I thought of him as Davy Crockett in a wheelchair, and we first glimpse him sitting in that chair on a railroad track, reciting “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” to the rising sun—and then daring an approaching train to hit him. I loved that old man. He was as real to me as anyone I’ve ever known.

Keith, of course, did go gentle into that good night. By choosing surgery, he chose to live, but he was completely accepting of the possibility that his time had come. When Sonja and I spoke to him the week before we lost him, he said to us that he’d had a wonderful life and had no complaints at all. And as he reviewed his life with us, there was that familiar, gentle laughter—the perpetual amusement, laughter in this case at his own infirmities, at the weight he’d picked up late in life: “Who could believe it? I was such a skinny kid.”

Keith laughed at himself, at life, and at death. He embraced the possibility of death as fully as he had embraced life, going gently into that good night. And I loved him for it as much as I loved my old man in that wheelchair daring the universe to strike him down.

He lived and died by his own words. He was, quite simply, the best.

Dan Bronson

DPU colleague, friend, and Hollywood screen writer

taught at DePauw University 1971-’79

participated in the Program for Keith's Remembrance Gathering, May 10, 2014

Tehachapi CA.