Tributes

Leave a tributeWell, I had to teach myself microautoradigraphy. But Steve and the Sherr’s were fundamental in my stay being fruitful. Barry appeared pretty soon in my office proposing a collaboration. He and Ev would measure protist feeding on bacteria using their recently developed epifluorescence technique and I could measure bacterial production with thymidine so we could compare both. Of course, being alone in an island where the only possible entertainment was to torture the alligators (Barry said), this collaboration was a most welcome suggestion. It was a lot of fun to share samplings around the island, experiments and discussions.

Then, my wife Cristina came to the island for the last month of my stay. Our relationship with the Sherr’s deepened. It was warm and interesting. Barry had a special sense of humor, full of irony, that both Cristina and I enjoyed thoroughly. He had an apparently quite critical and controversial attitude, but actually he was endearing. Our conversations were always interesting. None of the politically correct garbage. We talked about science and about Israel, about Sapelo and Spain. There was always a stimulating comment, an original point of view, something to ponder more carefully. In short, if our stay in Sapelo was a success, both scientifically and in a human sense, it was in a great proportion due to Barry an Ev.

We saw each other more times, usually at meetings, but the intense relationship of those months unfortunately did not have another chance. Through the years I have always admired the relationship between Ev and Barry. I believe they were the epitome of what a human couple team means. Cristina and I have tried to follow their example in our relationship all these years. So, given that we all have to die, doing so after a life full of professional achievements and doing so with your life partner at your side, I think is the kind of death I would like to have. Barry, rest in peace.

Thank you so much for all the interesting and revealing stories about Barry and your life with him---his growing up in New York, college in Kansas, interesting times spent on Sapelo Island and in Israel and people I have also crossed paths with, Marcelino Suzuki for example and Igor Melnikov. I recall reading a paper you both had written about stable isotopes when I was a graduate student in the 1980s, so it was quite meaningful to me to have the chance to work with you professionally 20 years later during the Shelf-Basin Interactions program in the Arctic. I recall at the time we didn't know for sure what we would be able to do with so many scientists aboard the then-new icebreaker Healy. It was only through the efforts of everyone involved including you and Barry and the Coast Guard that so much was accomplished in that program and also the Bering Sea Project in which we all participated. These programs remain excellent examples of scientists working together to get at the serious problems we face with climate change in the Arctic. Thank you again and may peace be with you at this time when we remember Barry's impact and life.

I am thinking about you and sending love.

Among my treasured memories are the times spent with you and Barry, especially the years on Sapelo. The antics, fellowship, trips-so many wonderful times!

Peace to you and the boys in this difficult time....

Lorene Townsend Howard

Leave a Tribute

Please be patient.

Please be patient.

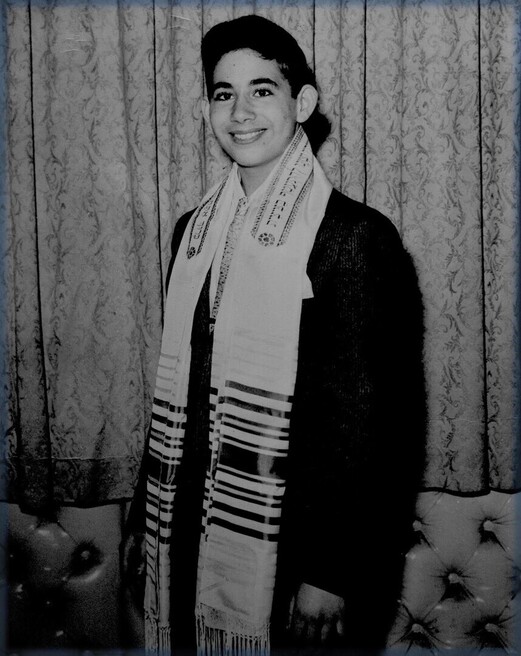

Yiddish in Blazing Saddles

The scene came on in which Mel Brooks as a Sioux. Indian chief (with a nod to the practice of casting jewish actors as Indians in western films), confronted a lonely wagon of black settlers on the Oregon trail. Brooks started spouting Yiddish: 'Shvartses! (Blacks!) (To Indian raising tomahawk): No, no, zayt nisht meshuge! (Don't be crazy!) (Raising arms to the heavens in stereotypical Indian pose): Loz im geyn! (Let him go!)'

Well Barry couldn't help letting out a loud guffaw at the unexpected Yiddish, which of course he was familiar with since his dad and grandparents spoke it. He said a couple of others in the theater laughed too, but most of the audience probably thought it was some sort of Native American language.

See the clip at:

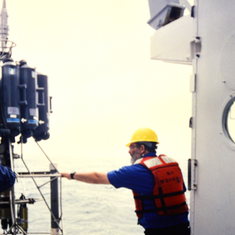

Old Fashioned Oceanography

Eastward was called the oceanographic training vessel for good reason. She was only 117 feet long, with a round bottom, and rolled something awful even in moderate seas. ‘Barf Bucket’ was an unofficial label Eastward deservedly earned. This was the only research vessel on which Ev saw a cruise participant literally turn green from seasickness. That was in June 1972, during one of Pomeroy’s class and Ev’s research cruises, when Hurricane Agnes churned from the Gulf of Mexico over Florida and across coastal Georgia, building up high waves over the shelf where the scientists were sampling. The incessant rolling and alarming jolts when a huge wave hit athwart the ship, combined with diesel fumes wafting up the corridor of the scientists’ cabins, were just too much for queasy stomachs.

Larry Pomeroy, who was the head scientist on that 1972 cruise accompanied by marine science graduate students, wrote about this episode in a memoir about oceanography on Eastward, posted on his memorial web page:

'On one occasion we found ourselves in the edge of a hurricane off Brunswick, Georgia. The eye of the storm was reported to be in the Gulf of Mexico, but even where we were the wind was lifting sheets of water from the sea. Sea and sky came together in a white shroud of blowing water. Visibility was zero and radar could not function. Sandoy (Eastward's captain) radioed his port captain, George Newton, in Beaufort for permission to dock in Brunswick because of the storm. The port captain was mystified by this request, because, he said, the storm was in the Gulf of Mexico. Radio exchanges went on for some hours until finally the port captain relented, and Sandoy summoned the Brunswick pilot. We waited in the blowing water. Finally, the pilot radioed that his boat was taking too much water, he was in danger of sinking, and he could not even locate us. He was going to have to turn back.In his heavy accent, Sandoy said, "I think I'll go south." We went rather slowly and blindly southward by compass, more or less toward the hurricane. Off northern Florida, we found a patch of relative calm, as one does far from the storm center, and without consulting anyone, Sandoy made a run into the nearest inlet and docked at Fernandina. We stayed there three days, spending all our money—on beer, mind you—in a brothel called the Palace Saloon. The eye of the storm passed nearby during those days. Then we went on with our cruise, except for one graduate student who had taken the first bus home.' (Note – that was the student who had turned green before the ship went into the port, he decided on a land-based career after that experience.)

Oceanographic sampling on Eastward was a holdover of methods used before CTD (Conductivity-Temperature-Depth) rosette sampling packages and computer logging of data were universal on research ships. Temperature profiles were determined by sending down a continuously recording bathythermograph (BT) instrument or a reversing thermometer for each depth.To collect water samples, separate hard plastic Niskin bottles were hand-hung on a metal wire on one side of the ship, and lowered to specific depths.The bottles were snapped shut to collect a sample of seawater at each depth by manually placing and sending down on the wire a heavy brass messenger, which popped the top bottle, releasing the next messenger to close the bottle hung below it, and so on to the last bottle on the wire.Needless to say, hanging 8-liter bottles on a wire when the ship was rolling and waves were breaking over the railing was a challenge.If there was a current tilting the bottle package away from vertical, the wire angle had to be determined to calculate the exact depth of each bottle. Taking the full bottles off the wire and carefully walking them to the bottle rack was even more daunting in a heavy sea.After racking and securing the Niskin bottles, separate smaller sample bottles were filled from a nipple at the base of each bottle for different analyses: glass salinity bottles, plastic bottles filled and frozen for later nutrient analysis, bottles for chlorophyll determination, large polycarbonate bottles for particulate carbon and nitrogen samples. Salinity and chlorophyll were analyzed between sampling stations during the cruise.

Seasickness is experienced by most sea-going oceanographers. Usually scientists would be nauseous the first day, and then get accustomed to the ship's motion. But stormy seas brought back the woe, first as overproducing salivary glands, and then a desire to heave.PESR watch duty, which all the crew had to stand up on the bridge, was the worst. The Precision Echo Sounding Recorder, or PESR, sends bursts of chirping sound; the echo returning from the sea bottom is picked up by a hydrophone, and the time differential between the chirp and its echo is converted to a measure of depth electronically. As the ship steams, the PESR continuously draws a contour of the sea bottom by a hot wire on a broad chart of moving paper. The PESR task was to monitor the output and label the ship's depth chart as it un-spooled with the date, time and position. The exaggerated motion of the upper part of the ship, combined with the smell of burning paper and electronics in the small instrument room as the depth was continuously monitored, was often just too much. When scientists got too ill, they would repair to their bunks, as lying down quieted the sensation.

Research ship food varies with the ship and the cooking staff. On Eastward Howard Wilson and Clyde Everett labored in the tiny galley at the rear of the ship to provide three calorie, fat, and salt-laden down-home meals for the scientists and crew each day. Breakfast usually included plate-sized pancakes, eggs, sausage or bacon and freshly baked biscuits.Lunch and dinner presented various fried or sauce-covered meat entrées with overcooked vegetables. When steaks were on the menu, Barry observed Howard liberally salt the cuts on both sides before frying them in a pan. Dessert was ice cream or pie - sweet potato pie was a favorite. Sometimes, though, the cooks would go trolling between meals and there would be fresh fish for dinner. Those working at night could raid the pantry for saltine crackers, peanut butter, and sardines. The cooks were berthed below deck in the most forward part of the crew's quarters. The ship's bow, of course, had the most violent motion in heavy seas, and the cooks would risk being tossed from their bunks.In those conditions, they would evacuate aft to the galley and sleep on the padded benches of the dining area.

Of course, there were moments of delight on the cruises when the seas were calm.I t was always a thrill to look around and not see land or a single other ship, and have the sense of being in a watery wilderness, far removed from civilization. When the Eastward was underway bottlenose dolphins would be attracted to the ship’s bow waves, and the crew would stand at the rails looking down at the elegant forms torpedoing along or splashing in and out of the standing waves on either side of the ship, obviously having great fun.The ship also stirred up flying fish, which would leap out of the waves ahead of the track and skim the ocean with fins outstretched for long seconds.Gulls and terns often flocked aft to snatch small fish and squid churned up by the propellers. When the ship was far from the coast, at the edge of the Sargasso Sea in the central North Atlantic, scientists scooped up clumps of sargassum weed floating on the surface with a bucket attached to a rope flung over a side railing. Then the golden-brown seaweed was put into clear glass jars to view the myriad fish, shrimp, and other sea creatures sheltering among the algal strands. Some endemic species, like the sargassum fish, had color patterns and body appendages to mimic the hues and patterns of the seaweed, perfectly camouflaged in their floating home.

Watch YouTube videos of a 1972 Eastward cruise that Ev participated in to see old fashioned sampling in action:

WOE 15 Science and the Sea Parts I and II

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E2fSCDKMruY

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EO_9iBtZPyk

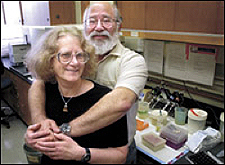

Valentines Day artlcle about Ev & Barry in the Corvallis Gazette-Times

Couple loves every minute

Pair of OSU science professors share close to every waking moment together

By THERESA HOGUE Gazette-Times February 14 2004

For some couples, the secret to a long-lasting marriage is maintaining a certain independence, a special piece of life that is separate from the other partner's.

Some even take separate vacations, and most at least have a job or hobby that takes them away from their house, and their spouse, for at least part of the day.

But when you ask Ev and Barry Sherr about taking time off from each other, they exchange confused glances. The two Oregon State University professors of oceanic and atmospheric science work side by side all day, and go home together at night, and never complain that they're seeing too much of each other.

"We're used to being together," Ev says, her eyes locking with Barry's. "It's hard for us to be apart."

Barry is a little less sentimental. He can think of plenty of times that they're not together.

"When we come home, I sit on the couch and watch TV while she's in the kitchen," he volunteers as proof of their time apart.

Ev and Barry haven't been apart too often since they met 30 years ago. At the time, Barry was a Ph.D. student at the University of Georgia, studying estuaries on Sapelo Island off the coast of Georgia. Ev was a post-doc researcher who came to Sapelo as a senior scientist on the same project.

When they first met, they were each married to other people. Ev's husband was also an academic, who lived on the mainland while Ev lived on the island. Barry's wife was living far away as well, and neither couple was spending much time together.

Work was the focus for Ev and Barry for the first few years, as Barry worked on completing his degree, and Ev was busy with her research. But once Barry finished his course work, he returned to the island, and love began to grow.

Both marriages had subsequently fallen apart, and the island, isolated and beautiful, was a natural backdrop for their relationship.

"It was a magic place," Ev said. "There was a deserted beach, and because it was isolated, it was a pretty romantic place."

While their first marriages had dissolved in part because of distance, their new relationship grew because of their proximity, and a shared passion for oceanography.

When Barry got the opportunity to do post doctorate work in Israel, they decided to marry, making it easier for them to travel together and live abroad. Ev took a year and a half leave from work on the island, and they flew to Israel just a week after their wedding day, Sept. 11, 1979.

Barry, who admittedly is a little light on romance, pointed out that the date of their anniversary is now a hard one to forget.

After completing his work in Israel, Barry returned with Ev to the island, where they continued to live and work from 1981 until 1990. They adopted one child, Aaron, in 1982, and nine months after his adoption, Ev discovered she was pregnant. Their second son, Jared, is now a freshman in physics at the University of Oregon.

The children led a sheltered life on the island, which had few inhabitants and no school. The boys had to take a 45-minute boat ride to the mainland and another 45-minute bus ride just to get to school.

"We wanted to get off the island," Ev said. "But the problem is working together as a research team, it's not that easy to find a job."

Oregon's higher education system has a history of supporting duel-career couples, and when a position opened up at OSU, the Sherrs jumped at the chance. The university allowed them to split the position between them, allowing the couple more time to raise their family.

Ev said their colleagues don't understand how a married couple can survive being together 24 hours a day, but Barry shrugs it off with a little chuckle.

"You can get used to anything," he joked. "Time flies."

Research does occasionally split the couple for a few months, including the time Barry spent half a year on the Arctic Ocean. Ev has two 40-day cruises to go on this year, which Barry said he's "not looking forward to."

"Mainly because I'll have to take care of the dog and the house, and our eldest son moved in with his cat, so now we have a grand-cat," Barry grumbled. He didn't mention the part where he'd miss Ev, but he didn't have to.

When they're apart, the couple e-mail each other daily, and have even discussed digital cameras attached to their computers for video conferencing.

As for Valentine's Day, the couple has no big plans. They don't exchange gifts or make a big deal out of the day. In fact, the most romantic gift Ev can recall receiving is something Barry and the kids gave her for Mother's Day a few years ago. Her eyes lit up as she recalled the "wonderful" present.

"They gave me a pressure cooker!" she said. "It was exactly what I wanted. I don't want jewelry."

It must be true love.