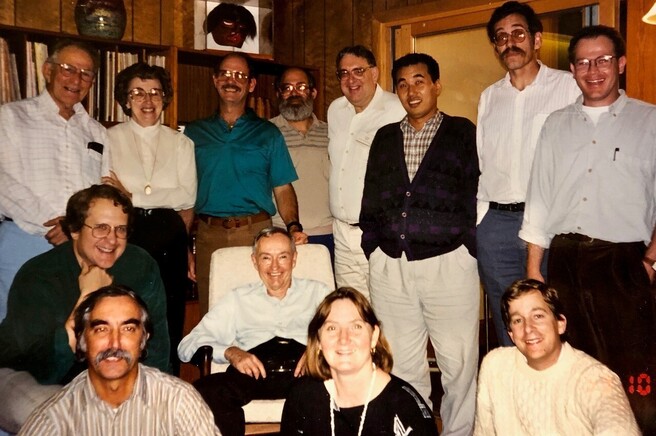

My academic introduction to coastal ecosystems was at Sapelo Island and the Georgia Marine Institute (Sapelo) by way of the fortuitous relationships with the University of Georgia faculty as a graduate student in the Ecology Program - then within the Department of Zoology. The Ecology Program later became today’s Institute of Ecology. Dirk Frankenberg, Bob Johannes, Gene Odum, Larry Pomeroy, Jim Schindler, and Bill Wiebe were not only scholarly scientific guides but also lively, kind, firm, and “to the point” about what a scientific career might bring to the life of those not yet steeped in the lore of science. I must have “underwhelmed” them many times. I have more patience with my students because of these UGA faculty because I have come to appreciate that they did the best they could with the meager resources this student brought to them.

Larry was one of the brightest ecologists, and one of the most professional. Peruse his co-authors’ names and you will recognize them as accomplished scientists who would not long tolerate mis-adventures or light thinking. He maintained a sharp attention to scientific issues as evidenced by the dry academic metrics used to measure citations, or whatever. Larry’s presentations at professional meetings were always well-prepared, polite, and entirely credible, as well as embedded with a sense of quite enthusiasm. He didn’t arm-wave or entertain, but he did challenge you in his quiet way. There are few people like him who have are so capable of bringing out the intellectual side of science in a way that advances the science and promotes openness to the questions lying unanswered beneath the superficial surface of grantsmanship and generating a c.v. addition. His writing skills were exceptionally well honed, which also reflected Janet’s writing skills. In private conversations he was equally honest and helpful, while accommodating critical remarks from those of opposite views. He did not mince words, and was thoughtful and to the point. As someone about him; “When Larry talks, people listen.” As he said “it is better to hear it from your friends beforehand, than from the critics after it is published and cannot be changed.”

His first Science paper was on phosphorus cycling, and there was another on the temperature limits of Arctic food webs. His work on phosphorus cycling turned the nutrient cycling perspectives on that element inside out - rather than being a slow turnover, it was incredibly fast, and mediated by the smallest, not the most conspicuous organisms. His paper in BioScience on the “microbial loop” is a classic. He was one of the first to promote and use high-quality modeling of food webs, brought to fruition one of the first syntheses of salt marsh ecosystems, and had a continuing interest in the connections between continental shelf waters and both estuary and deeper waters.

He was Director of the Sapelo Island Marine Institute, after which its primary vessel at the time was named ‘Janet’ who was such a great partner. It was probably a trick to keep her at Sapelo longer. A determined field scientist, he once putt-putted his outboard back to the laboratory in Chesapeake Bay with the motor in reverse, taking several hours to return, but without inconveniencing anyone by asking for assistance. He taught students by example that it was often not necessary to go much further than the hardware store for supplies or your backyard to learn something about the fundamentals of how ecosystems ‘work’ to cycle nutrients. His few expensive toys were the means to get an answer, and were not the focus of his attention, for Larry believed in a data-rich and thoughtful analysis. He was un-constrained by what was ‘supposed’ to be the understanding of things, especially if it was different from what his experience was. And if he saw what was really going on -- as he did with the role of microbes earlier than almost everyone -- he would not give up.

He had a sharp and wry sense of humor and potent powers of observations that, thankfully, kept him out of the Dean’s office, despite repeated attempts to get him there for a term or two. One time he succinctly and humorously stopped the audience of microbial ecologists from going into a cul d’sac of logical superfluousness by pointing out that their attention was drifting into questions about the microbes in the ungulate’s stomach, rather why the cow was in the pasture in the first place.

Larry introduced graduate students to Liebig's Law of the Minimum -- what it was, might be, and wasn’t. Liebig’s Law stated that plant yield was proportional to the limiting nutrient supply. As the limiting nutrient was supplied, another nutrient became limiting, and so forth. This law was then widely credited to the German chemist Justus von Liebig (1803-1873), who also challenged the prevailing assumption that soil humus was the source of all nutrients. But it was Carl Sprengel (1787-1859) who is now considered to have formulated the Law of the Minimum, and for disproving the humus theory of soil fertility. Liebig, it seems, was not at all shy about taking credit for the work of other’s, whether by failing to offer credit or by force of his strong personality. That aspect of Liebig’s persona was not something a graduate student wanted to hear. However, Larry then balanced that negativity with the observation that Liebig put his students in the laboratory to do their own work and to generate their own observations and data. Liebig’s students listened to the Herr Professor in lectures and made their own observations in the laboratory. They became more engaged in their profession through the laboratory experience and were better professionals because of it. Larry made these points about professionalism, gaming the system, personal responsibility, and teaching efficacy in a few brief remarks about someone’s work of 100+ years earlier. It was an effective discussion by a warm human being trying to make the world a better place.