WHEN TENNESSEE'S WHIRLWIND OF A COACH, PAT SUMMITT, HITS YOU WITH HER STEELY GAZE, YOU GET A DOSE OF THE INTENSITY THAT HAS CARRIED THE LADY VOLS TO FIVE NCAA TITLES

Here comes this lady into your life. You don't know that she has been up all night peeing, racked with pain in her lower back. You don't know how many people told her she was nuts to get on an airplane and fly to your hometown at a time like this. You don't know that an hour ago, when her water broke, she was crouched in an eight-seat King Air, blotting her legs with paper towels. Hell, you're

16. You don't know she's spitting Nature in the eye and kicking Time in the teeth.

She's sitting on your sofa as you come through the door from school on a September day in 1990, and she grins and grinds her teeth against the contractions. How could you know that it's already too late—that Pat Summitt's got you, she's got you forever?

Michelle Marciniak takes a seat and looks around her living room. She's a senior at Allentown (Pa.) Central Catholic High, an hour north of Philadelphia, a guard who in six months will become the Naismith and Gatorade player of the year. But that's not enough for Michelle. In her dream, she has

both the acclaim and love that go to the best player in the land

and the championship that her high school team keeps falling short of. She would love to put her dream in Pat's hands, but in Pat's hands already rests the

other player of the year candidate, the

other All-America who plays Michelle's position.

Michelle knows something weird is going on the minute she walks in the door . . . but what is it? Her mom, Betsy, and her older brother, Steve, are wearing the same nervous, crooked little smile. Michelle's cocker spaniel, Frosty, is yip-yapping laps around the premier coach in the history of women's basketball. Pat's bouncing from the sofa to the bathroom to the telephone and back. Her assistant coach, Mickie DeMoss, is whipping through Tennessee's recruiting scrapbook as if she were sitting on a mound of fire ants:

Here's the arena, here's the library, here's the '89 national championship—O.K., Michelle, any questions? Michelle's dad, Whitey, is sitting across the room, jingling coins manically in his pocket. You try it. It's not easy to jingle coins while you're sitting down.

Suddenly Nature mounts a furious comeback, Time starts kicking Pat in the teeth. "Mickie," she blurts, "we have to go. Now." Suddenly they're babbling to the teenage girl that Pat's baby is coming, and Steve and Michelle are racing to his car to lead the Tennessee coaches to—to the hospital, right?—heck no, to the airport, because Patricia Head Summitt is going to have this baby when and where she wants it. Suddenly Steve and Michelle are swerving around curves, blowing through red lights and stop signs and do not enter signs, swiveling their heads to look back at Mickie, who's freaking out at the wheel of the rental car, and Pat, who has her feet on the dashboard and is groaning. They all screech to a halt near the airport's private hangars. Mickie runs up the steps into an airplane. Wrong airplane. She pops back out. "I'll call you!" Pat shouts to Michelle. She strides into the King Air, and off she roars into the sky.

There are a hundred ways to write a story about a hurricane. We could watch it gathering shape and strength from afar and chronicle its course. We could follow at its heels and document its wake, or attempt to speak to all who experienced it and make a mosaic of their impressions. But perhaps the most direct and true way is to see and smell and feel it through one person—one girl who ran both from it and straight at it; one girl sucked into its eye and then set down on its other side; one girl, now a woman, who has had time to sort out what it did to her life.

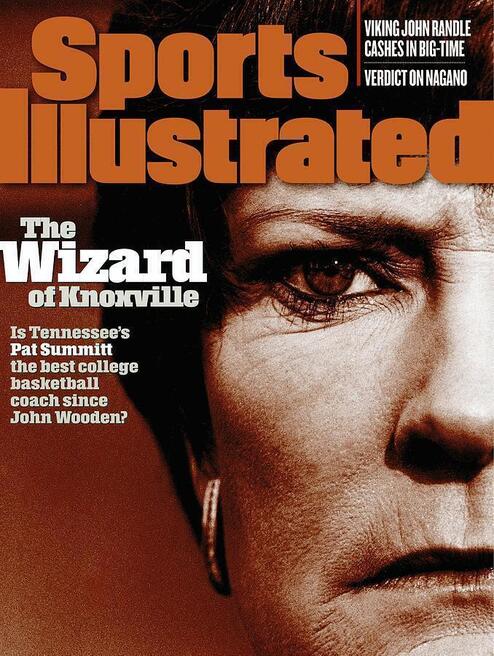

Those who are playing for Pat Summitt now at Tennessee—members of the 1997-98 team, which finished the regular season 30-0 and is favored to win an astonishing third consecutive national title, the sixth in 12 years—cannot see the hurricane clearly because they're still inside it. They're hugging a tree for dear life, waiting for the wind and water to recede. Someone else, on a dry, sunny day a few years from now, can ask them to describe what it was like to play for this woman whose five national championships are surpassed in NCAA basketball history only by John Wooden's 10; whose .814 winning percentage in 23 seasons ranks fifth among all coaches in the history of men's and women's college basketball; whose number of trips to the Final Four, 14 and counting, will most likely never be matched, seeing how she's only 45. This woman who never raised a placard or a peep for women's rights, who never filed a suit or overturned a statute or gave a flying hoot about isms or movements, this unconscious revolutionary who's tearing up the terrain of sexual stereotypes and seeding it with young women who have an altered vision of what a female can be.

So we'll leave her for now, we who can't grasp yet what women like her will mean to the rest of us. We'll leave her doubled over in pain on an airplane, clenching every muscle she's got, trying to recall everything her mother told her about birthing babies so she can do the opposite until she's back on the ground in Tennessee. And we'll return to the teenage girl by the phone, awaiting Pat's call, trying to fathom what this strange day portends.

It's so hard when so much air has leaked out of your dream, to inflate it again. For the previous two years, whenever Michelle was frustrated or angry on the court, whenever her high school coach yanked her midway through the third quarter because he didn't believe in stars or 40-point scoring nights, all she had to do was look up in the stands and see her mother forming that little T with her forefingers. It meant Tennessee, but it really meant Pat. It meant NCAA championships and All-America honors and Olympic gold medals, because that's what girls got when they were handpicked by Pat.

Ever since that day in December '87, during her freshman year, when Michelle persuaded her mom to take her on an unofficial visit to Knoxville and she watched this tall, handsome, crisply dressed woman coach a game and a practice, Michelle's aim in life had been to play for Pat. That practice had blown her mind; never had Michelle met a woman—hell, a

human being—so intense, so authoritative, so certain and yet so caring. Pat walked into a room, and everything about her—her ramrod posture, her confident smile, her piercing blue eyes and her direct manner of speaking—said, "I love what I'm doing and this is what I'm here to talk about, and you'll pay attention while I'm talking or you'll leave the room." Michelle could picture her as president—no, not of the university but of the country! And imagine this: Coach Summitt told her girls to call her

Pat!

For hours the teenager would thumb through her bible, a scrapbook full of photographs of Tennessee women's basketball and of warm notes from Pat. To heck with rival recruiters who warned her that Pat would snuff out her flamboyance on the court—envy, pure poison envy. She was going to play for the lady, case closed . . . until that afternoon in the spring of 1990, the end of her junior year. It was the day after Michelle's second unofficial visit to Knoxville, and on the way home she stopped in Hampton, Va., to play in an AAU tournament. She had decided it was time to announce her decision to the world when. . . .

"Did you hear about Tiffany?" It was her AAU coach, Michael Flynn, addressing Michelle just before she took the court.

"No, what about her?" said Michelle.

"She committed to Tennessee."

"That

can't be true! I was just there yesterday!"

"Well, it is. She committed today."

Michelle felt as if she were choking as if she might faint. Tiffany Woosley was the girl who would vie with Michelle for every player of the year award during their senior seasons. A Tennessee girl, for crying out loud, who played point guard, the same position as Michelle; no way there would be playing time for two freshman guards! Pat must have betrayed her! Pat must have tipped off Tiffany that Michelle was about to commit, and now Tiffany was the first one, the special one, the local hero with the inside track, and Michelle's dream was up in smoke!

She cried her way up I-95 on the journey home. Bitterly she studied the list of 200 other universities offering her scholarships and searched for a team with no dictator, no system to submit to, somewhere she could play the splashy, spinning, behind-the-back-and-between-the-legs game she loved, light it up for 30 a night and stick it to that cruel lady who. . . .

Who now, six months later, has just hopelessly muddled Michelle by nearly dropping a baby in her lap! "If she didn't really want me, why did she go through all

that, Mom?" Michelle asks as the two sit up past midnight, waiting for Pat to call. Michelle has always believed in omens, in signals from God. "Maybe this means I was

meant to go with her," she says. "I almost feel like I'm the godmother of this baby."

At 1 a.m. the phone jangles. It's Pat, calling a 16-year-old player a half hour after giving birth to a boy. It's Pat, whose doctor has just told her that it was only because the baby's head was turned sideways in the womb that she didn't deliver him into the hands of an assistant coach at 20,000 feet.

"Congratulations!" cries Michelle. "I can't believe this! Thanks so much for calling me! Goodbye! Congratulations, Pat!"

So Michelle signs with Pat and becomes an All-America guard at Tennessee, correct?

No. When Pat pictures Michelle, she sees so much of herself—the girl who would challenge boys to races and arm-wrestling matches and tackle football. Pat can't bear to disappoint Michelle, so she tells her that she wants her very much, but she can't promise her playing time or stardom. So Michelle agonizes, Michelle flip-flops, Michelle visits Tennessee a third time, hugs Pat, kisses the new baby . . . and signs with Notre Dame. And waits all of two weeks into her freshman season to break NCAA rules by calling Pat to tell her she has made the biggest mistake of her life, and how unfulfilling it is to be the star of a confused and divided 1-5 team, and how she wants to transfer right this very minute.

Pat reports the violation, but Michelle, stubborn as fungus, calls her again, and . . . well, almost everything between this lady and this girl is going to be complicated and racked with labor pains, so let's jump forward a year and a half, leap over Michelle's transfer to Tennessee and the season that, in keeping with NCAA rules, she has to sit out as penance for the switch.

It's the fall of 1993, and Michelle finally is living her dream, and here is how the dream begins: It begins with 4:30 a.m. wake-ups, with relentless wind sprints through the dark on the Tennessee track. It begins with the frightening realization that there is no excuse, none, a fact that team manager Todd Dooley learns the morning he awakens crumpled by stomach cramps and forces himself out of bed to show up at 6:30 and tries to explain to Pat why he's a half hour late, only to hear her shout, "You don't ever be late! Next time you just bring that toilet with you!"

It begins with Michelle walking into the Lady Vols' locker room complex and stopping to stare at all the framed photographs on the National Championship Wall and the White House Visits Wall and the Final Four Wall and the All-Americas and Olympians Wall. It begins with Pat reminding her, sometimes even testing her, about who it is up there on the walls, who it is she owes excellence to. It begins with Michelle knowing that Pat kicked the 1989-90 Lady Vols out of their palatial locker room for five weeks and squeezed them into a tiny visitors' dressing room. They hadn't deserved the palace. They hadn't worked hard enough.

It begins with Michelle looking over her shoulder as she dribbles in a scrimmage and wondering what in blazes this woman is doing, three feet behind her, down on one knee and squatting lower and lower as if the view at sneaker level might reveal some hidden flaw, slapping the floor with her palm at her latest find, hanging on Michelle's next decision as if life itself were riding on it, leaning right with her as she cuts and leans in for a layup, and then, daggone it, the anguish squinching Pat's cheeks and shaking her fist if Michelle misses, the disappointment even sharper than Michelle's. And the thing is, that intensity never flags, not for a day or an hour or a minute. Suddenly, in the midst of a seemingly splendid practice, Pat might shout, "Hold it! Stop! Everyone stop!" and stride toward Michelle, the way she strode one day toward forward Lisa Harrison.

"Lisa!"

"Yes, Pat?"

"What have you done for your team today?"

"Well, uh . . . I . . . I don't know."

"That's exactly my point!"

Whoo boy. Who else demands that her players sit in the first three rows of their classes and forbids them a single unexcused absence? Who else finds out about every visit they make to the mall for a new pair of jeans, every trip to a restaurant or a movie, and always mentions it the next day, so that it seems they can do nothing without her knowing it? Who else, at the end of a three-hour practice, times the suicide sprints on the big scoreboard clock? Who else films every practice and then sits through it all over again, so that if a player is fool enough to question a single one of her criticisms, Pat takes her right to the videotape in her office and stops the dang thing so often to prove she's right that it takes an hour to cover the first 10 minutes? Who carries five VCRs on road trips and watches tape of her opponents while she works out on the treadmill while she scribbles points of emphasis on a notepad while she talks on the phone with an assistant—all after she has read a book to her son, Tyler, and put him to bed?

Imagine living with that. For the longest time even Pat couldn't imagine who could imagine it, until she found R.B. Summitt, whom she married in 1980, her sixth season at Tennessee. A man secure in his own profession as vice president of his family's bank, a man born to the first female pilot in Monroe County, Tennessee, a man unthreatened by a woman with a life all her own. Sure, sometimes he goes off the deep end in the heat of action and yells things at opposing teams that she wouldn't, but Pat can live with that. She knows what it is to enter another realm during a game. For her, it's the one time when Time lets go of her, when it even seems to stop.

Yes, Michelle could almost smell what the pair of Vanderbilt researchers found when they hooked up some visiting coaches to a cardiac monitor one year back in the '80s. Pat's heartbeat and blood pressure, the fastest and highest of all the coaches' during the action on the court, plummeted when a timeout was called, to the lowest of them all. There's no huddle you would rather be in with 20 ticks left in a tie game. First, Pat would tap the 60-plus years of coaching experience with which she surrounds herself, consulting swiftly with her staff: DeMoss, with her uncanny ability to see what all 10 players were doing on the floor; Holly Warlick, who had the game seared into her soul as Pat's point guard in the late '70s; and Al Brown, who could study video and spot the neck twitch that indicated that the opposing team's forward was about to drive left. Then Pat would make her decision, kneel on a stool in front of her players and pull them into her dead-sure eyes. The Lady Vols would drink in this calm, assurance and intensity. Ten players would walk back onto the court. Five of them knew that their coach had just given them the way to win.

Michelle is determined to be one of those five, to let Pat jump down her throat and pull out her dream. To nod and chirp "Rebound!"—as every Lady Vol is expected to do when she's corrected—louder than anyone. To look Pat flush in the eye because there's nothing that makes the lady crazier than a player who looks away from The Look, who tries to evade those two blue drill bits digging into her skull. Pat actually dips her knees, lowers herself to catch the girl's yellow-belly eyeballs, locks in on them and lifts them, and if that fails, she barks, "Look me in the eyes!" She wants to see the girl's eyes blaze right back at her, to say, "All right, lady, I'll show you!" To blaze like hers did back when Daddy would inspect the tobacco plants from which she had been pulling suckers for eight hours under a 90[degree] sun and find the one damn sucker she had missed—that's what Pat wants to see. In a critical moment, if she doesn't get what she wants, her neck goes blotchy red, and a vein pops out, and you can look at it and see her heart kicking.

Michelle will do anything to appease that heart. She'll go over, under, through any obstacle and come up pumping her fist. Crash, her teammates start calling her, and the Tennessee basketball fans love her. She'll hang out at Pat's office like a faithful puppy, write Pat birthday and Christmas and Mother's Day cards. She'll stick a note on the windshield of Pat's car a week before practice, saying,

Eight more days! I can't wait! and make Pat grin for an hour—heck, sounds exactly like something Pat would say! She'll do anything for Pat . . . except give up her game.

It drives Pat bonkers. She leaves her office and jogs across campus, wondering, What is it with this girl? You keep telling her to slow down, to make better decisions, to forget the spin move, to throw the simple 10-foot chest pass instead of the blind 40-foot bounce pass, and she keeps nodding her head, but 30 seconds later, there's the dang thing again! Never met a girl so strong-willed in my life.

One day a man named Bill Rodgers, a Knoxville car dealer whose passion and part-time occupation he calls "performance enhancing," looks at the results of the Predictive Index personality test he's administered to Michelle and Pat. "It's amazing," he tells Pat. "It's like looking at a young

you. Michelle's more concerned with image, with wanting to be loved, but as for almost everything else—ambitious, competitive, outgoing, leadership, stubbornness, willingness to take on all the responsibility under extreme pressure—you could literally be mother and daughter!"

The bond between them keeps deepening. Pat just smiles. If Michelle is just like her—well, then, Pat knows just what to do. She'll ride her harder still, harder than she's ridden anyone before. "

Defense?" Pat hollers. "You call that defense, Michelle? I thought you wanted to be a leader. How can I take you to war with me?

Don't try to tell me! I've been coaching longer than you've been

alive!

Pat would never cry; when she did as a child, her daddy only spanked her harder.

"You're gold-digging again, Michelle! Are you going to

be the showboat or be

on the showboat? Well, I'll just sit you, Michelle. Because I know you love to play and

hate to sit—right, Michelle? That

kills you, doesn't it, Michelle?"

In front of anyone, this could happen. In front of 10 strangers, Knoxville business leaders and their spouses were invited into the Lady Vols' locker room as "guest coaches" on game nights, most of them staring at the floor and praying Pat doesn't suddenly turn on

them.

She half kills Michelle that first year. Makes her sit for half of every game as a backup shooting guard, sit and watch Tiffany Woosley run the team at point guard. Michelle's determined not to cry in front of Pat, because Pat would never cry; when she did, her daddy only spanked her harder. Michelle digs her top teeth into her bottom lip when Pat tears into her. It's the same thing Pat has done so many times in her life that there's a little indent on the right side of her lower lip. Michelle turns away and grinds her teeth—how could this be happening to the girl who won the Greg Tatum Award in eighth grade as her school's most Christlike child? She holds everything in until she gets home, then cries her eyes out. She drives her red Honda to a stream in the Great Smoky Mountains near Gatlinburg, sits and listens to the water and thinks, What is it with this crazy woman? I'm giving everything I have, but everything's not enough for her. There's something driving her, bigger than what drives anybody in the world. What is it?

It's growing mutually, magnetically, their frustration with and affection for each other. If Michelle could just pigeonhole Pat as the tyrant, it would be so much easier. But Pat's the woman you wish you could cook like and water-ski like and chat up the cashier like and toss off one-liners like. Pat's the life of the party.

How does she do it? How could she turn your name into an obscenity on the court, then walk off it and become your mom? How could a woman be transformed that completely, so that when you sit in her office, she leans toward you to connect with you, the flesh around those piercing eyes wrinkling in concentration, and invariably asks what

you think the team needs and then, as you're getting ready to leave, asks if

you think her beige shoes go with her white skirt. Not to con you or charm you, because you would eventually sniff that out. She asks so intently that it seems the two of you are the only ones in the universe, so honestly that you smell the unsure girl beneath the awe-inducing coach.

Then, bang, you and she are done, and her eyes are flashing to her day planner, the one she keeps gorging with duties, 10:25 appointments crowbarred between 10:15s and 10:30s. All etched in perfect calligraphy, this hand-to-hand combat with Time, with neat arrows pointing to peripheral obligations that she can attend to simultaneously, without assigning them a minute of their own, with

key meetings underlined and very important appointments blinking exclamation points!!!! Soon Michelle and all her teammates are carrying day planners, opening them together at Pat's command to fill up a stray half hour here, a vagrant hour there, even to transcribe her annual reminder in late October:

Don't forget to turn back your clocks one hour! Soon it's an epidemic, this guilt over a moment lost.

Where's she from, this woman? What incubated her? Manhattan or Chicago? A surgeon daddy and a mama lawyer? No, people tell you. She's a

farm girl. A farm girl from middle Tennessee, where the sun is the clock, Nature calls the rhythm, and women know their place. "Take me there," Michelle asks Pat one day. "I want to meet your family and see where you grew up." Michelle's changing her major to psychology. She has to figure this lady out.

"Can't," says Pat. "NCAA won't let me take you. Someday we'll do it, Michelle. When all this is done."

So Michelle must play detective, cobble together scraps. The memories of Pat's former players, an anecdote from a newspaper article, the reply to a brave question she might throw at Pat. Little clues, like that scar on Pat's left knee. Slowly—it takes years—a picture begins to appear. A fuzzy, grainy picture. . . .

Of a face, a young woman's face, hair sweat-plastered around its edges. A young woman alone at night in a gym. She's running 15 more suicides because she missed a foul shot at the end of her two-hour workout. Pat has flung off her knee brace; it's a crutch, she tells herself, and she's never going to wear it again. Now you can see that scar, blazing red.

A year has passed since she tore her anterior cruciate ligament during her senior season at Tennessee-Martin. A year since the orthopedic surgeon examined the knee and told Pat, "Forget it." It's 1974, and many men playing big-time sports are finished after tearing an ACL. A woman? Just forget it.

Fix it, Tall Man told the surgeon. Tall Man is what the hired help called her father, Richard. Fix it right, he said, because Pat's

going to play for the U.S. in Montreal in 1976, when women will play basketball for the first time in Olympic history. Pat swallowed hard because until Daddy said it, she didn't know she was going to do that. When her best friend, Jane Brown, walked into the hospital room a few minutes later, Pat blurted, "That doctor's crazy as heck if he thinks I'm not going to play ball again!" Then everyone left her room, and she hobbled to the window, drew the curtains and cried herself to sleep.

Now she has to make Tall Man's prediction come true. She has to lose 15 pounds, rehabilitate her knee and work out twice a day to make the Olympics . . . while she's teaching four phys-ed courses at Tennessee, while she's taking four courses to get her master's degree, while she's coaching the women's basketball team. Three-mile run at 6 a.m., weights at 6:30, shower, rush to the gym to teach, dash to the lecture hall to take the exercise-physiology and sports-administration classes, sprint back to the gym to coach a 2 1/2-hour practice, hop in the car to go scout a local high school player, burn rubber back to the gym for two hours of basketball and sprints, shower again and hightail it home by midnight to study for the biomechanics midterm.

She's 22. She was hired to be the women's assistant basketball coach, only to learn a few weeks later that the head coach had resigned to pursue her doctorate. She has never coached a game in her life. She has no assistant. She's scared, the way she was that day when she was 12 and Tall Man dropped her off in the middle of miles of hay, pointed to the tractor and the hay rake and said, "Do it," then drove away. What's she going to do now, 10 years later? The only thing she knows. She'll be her father. Her players can be her.

At first it's glorified intramurals, a tryout sheet posted on a bulletin board inviting women to play in front of four or five dozen fans on a shadowy floor crisscrossed by badminton, volleyball and basketball lines. Pat digs in. She sweeps floors, tapes ankles, sets out the chairs and towels, washes the uniforms on road trips. She drives the team to road games in a van, her head poked out the window to keep her awake on the drive home at 2 a.m. Behind her, her players glance at each other when the rain stops and the windshield dries and the wipers keep squeaking, squeaking, squeaking. No one musters the courage to utter a word.

She doesn't lose 15 pounds. She loses 27. She sits on the edge of a table, pokes her foot through the handles of a sack full of bricks and lifts till her knee screams, but never when her players are around to see her. She makes the '76 Olympic team—a co-captain and the oldest player, at 24, on the U.S. roster that shocks the field and comes home with a silver medal. She takes the Lady Vols to the Final Four seven months later, in her third year as coach. She gets her master's degree in physical education. She has learned she can do it: She can overpower Nature and outmuscle Time—at least for a while, just like men do. She has learned, thanks to her father, about human will. How can she settle for filling her players with

want now that she knows the psychic power of

expect?

You think she's tough

now, Michelle? Oh, please, the Lady Vols with crow's feet tell her at the annual alumnae reunions. You should've seen Pat back

then! How about that time she found out we had that all-night party, and she set up trash cans at each corner of the court and ran us till we puked in them? How about that all-night, 8 1/2-hour drive home after we lost in Cleveland, Miss.—no stops, bladders and bellies be damned? What about the 2 a.m. practice after we drove three hours back from the loss at Vandy, the game Pat's father saw and told her he'd seen a better game the night before between sixth-graders? Yeah, ever notice how quick she was, after the games her father attended, to ask people, "What did my dad say?" What about that time we fell apart in the second half at South Carolina, went straight to the locker room when we got back the next day and had to put on those smelly uniforms that had been locked in the trunk all night, and Pat hollered, "Now you're going to play the half you didn't play last night!"

Pat leads the Lady Vols to the Final Four six more times over the next nine years—and wins none of them, her teams always just a little short on talent. Forget the first Olympic gold medal in U.S. women's basketball history, the one won by Pat's '84 team—heck, a half hour later Pat forgets it. Just imagine what all those fruitless Final Fours do to Tall Man's daughter. If you're Pat's roommate during the early years in Knoxville, before Pat has a husband at age 28 and a child at 38, before there are videos of opponents to watch until she's cross-eyed, you love it when another big game's approaching. Because when you wake up, the white tornado has struck again—the whole apartment's gleaming!

Price tag? Oh, you bet. Don't you think there are times, when the grease stain on the baseboard has her on her knees at 1 a.m., that she wants this thing that's got hold of her to let go? "Times," as Pat's brother Charles puts it, "when you want to knock Daddy's head off." Times when the pain from tension in Pat's left shoulder grows so sharp that she must schedule a deep massage—like, five hours before every game. Times when she's sitting on an airplane next to two women who are solemnly weighing the floral pattern against the plaid for the master-bathroom drapes, and their relationship to Time is so dramatically different from Pat's that she feels as if she's from another planet. Times when people talk about her as if she's a freak, as if she's a man.

Once, when she found out the players had an all-night party, she ran them till they puked.

As if she's, say, Bobby Knight. That's what they say when she seizes Michelle by the front of her jersey, twists it and snarls at her during the game against Louisiana Tech in the NCAA regionals in Michelle's sophomore year. The photograph runs in newspapers all over the country. "Spinderella and her wicked stepmother," the Knoxville press calls Michelle and Pat. From all over the country friends and relatives send the picture to Michelle and her parents, demanding,

What is this woman doing to Michelle?Pat flinches. Why, she wonders, can't people look at the photograph in context, why can't they understand that she's as swift to drop her whole life and rush to her players' sides when they have problems as she is to drop the roof on them when they screw up? That she's Miss Hazel's daughter every inch as much as she is Tall Man's? That she grew up watching and imitating her mother, who was the first to visit the sick or the dying, first to pick, pluck, prepare and deliver a meal of butter beans and fried chicken and mashed potatoes and homemade ice cream to the worried or the grieving?

Pat calls Michelle's mother to try to explain. "She's all yours, Pat," says Betsy, but privately she and her husband are aching for their child and wondering about Pat, too. Doesn't Pat understand that Michelle isn't just like her? Doesn't she know that Michelle's father is tough too, an old college fullback, but that every night he gave his girl a good-night kiss?

Life's funny, though, and something else happens in that 1994 NCAA tournament game after Pat grabs Michelle's jersey: Michelle grabs Pat's heart. She comes in at point guard when the Lady Vols are gagging in the second half, down by 18, and nearly saves them single-handedly before they lose by three. Furious drives to the basket, long jumpers, brilliant passes, knee-burning steals.

Pat sits there shaking her head, the truth moving from her mind into her gut. Michelle is the only one out there refusing to lose; the only one just like her! Pat can't wait. She tells Michelle right after the game: Tiffany's out. You're in. You're my starting point guard next year. "But remember," Pat says, "the point guard's an extension of me on the court. You've never been through anything like what you're about to go through."

Michelle goes home. She places one large framed picture of Pat twisting her jersey and snarling at her on her bedroom wall, and one small framed picture of the same scene on the dashboard of her car. Now Pat's everywhere Michelle goes, everywhere Michelle hides.

We've got an appointment, so let's break into a trot. Let's dash right past another year and a half; let's bully Time, the way Pat does. Let's fly by the day Pat throws her starting point guard out of practice in her junior year, past the day when Michelle finally crumbles and sobs in front of everyone. Let's jump clean over the last day of that same junior year, when Michelle comes within a whisker of her dream but loses in the NCAA title game to Connecticut—still unsure of herself on the floor in critical moments, still whirling between Pat's way and her way, no longer the All-America guard nor even the all-conference one.

There it goes—did you see it?—the day midway through Michelle's senior season when Pat makes her sit on a chair at midcourt, like a bad schoolgirl, and watch practice, then makes her move the chair to the far end of the floor after she whispers to a teammate.

Forget the Olympic gold medal won by Summitt's '84 team—heck, a half hour later Pat forgets it.

We've got an appointment to keep, an appointment with an ice storm in Mississippi, coldest night of Michelle's life. It's February 1996. Time's not ticking now for Pat and Michelle. It's hammering. Pat has fixed that problem she had of making it to the Final Four and losing, fixed it mostly by persuading the best recruiter in the country, DeMoss, to leave Auburn in 1985 and be her assistant. Pat has won national titles in '87, '89 and '91, but four years have elapsed since her last one, way too long, and she needs her team leader, Michelle, as much as Michelle needs her.

Michelle's desperate. It's her last shot at the title, her last shot to make all this pain pay off. Her last chance to regain the kind of national acclaim that vanished for her after high school, to become a player whom the two fledgling women's pro leagues will come looking for. But how can she? The Lady Vols are 17-3, but they look nothing like a title team—and guess whose fault that is?

Now Pat's team has gotten skunked a fourth time, by Mississippi, and Michelle has gone 0 for 7 from the field and fouled out, having played as if she could feel Pat's eyes burning through her back. The bus is crawling toward the airport, across the ice, through the darkness; crawling as Michelle listens to Pat, a few seats away, ridicule her; crawling as Pat rises and takes a seat next to Michelle and tells her that unless something drastic happens, she doesn't think the Lady Vols can win a championship with Michelle as their point guard. It's hopeless—no lip-biting can possibly dam it now that the gates are open, now that Pat has already brought Michelle to tears twice that day, at halftime and just after the game, and . . . here it . . . here it comes . . . the third wave of sobs.

Michelle doesn't sleep that night. She's terrified. For the first time she has gone past anger and frustration and the hunger to show Pat she's wrong. The girl with the brightest flame is dead inside. She cannot. Take this. Anymore.

At 6:45 a.m. she calls Pat's home. Only fear and despair could make her speak to Pat Summitt this way: "You don't think we can win it all with me playing like I am," she says, "but I . . . I don't think we can win it all with you coaching like you are. You've got to back off me now, especially in front of other people. You can't do that to me anymore." Her breath catches.

Maybe it's because Pat has won so many championships that she can be more flexible now. Maybe it's impossible not to soften a little, stop choking each minute quite so hard, when there's a five-year-old boy in bed breathing the night in and out while you listen and then wrapping you in a hug when morning comes. Maybe Pat has no real choice this late in the season. She and Michelle speak for a while, and then there's silence. Well? "Doesn't mean I won't criticize you anymore, do you understand?" Pat says. "But I'll try it."

With that, everything changes. "As if we were two people in a room with boxing gloves," Michelle will say a few years later, "who finally both come out with our hands up." Pat gives Michelle more rope. Michelle quits trying to tie a triple knot when a single will do just fine. Tennessee reels off 15 straight wins, beating UConn in overtime in the NCAA semifinals behind Michelle's 21 points and then blowing out Georgia to win the crown.

Pat goes up into the stands and gets the first hug and kiss from her father that she can remember. Michelle is chosen the Final Four MVP. Her flying leap into Pat's arms nearly knocks Pat off her feet.

If this were a TV movie, it would end there. You would never get the chance to watch Michelle go home with Pat and finally understand the force, or to gaze down the road and peek around the bend to where the story really ends. But it's not a TV movie. It's summer, four months after the title, and the two women are busting 90 through middle Tennessee, heading to Henrietta. It's O.K. with the NCAA because Michelle has just graduated, and it's O.K. with the state police because Pat Summitt can go as fast as she wants in Tennessee, and it's O.K. between Pat and Michelle, who cried together at the senior banquet a few months before.

From this new place, from this last ledge before Michelle leaps into the pros and adulthood, then maybe marriage and children, she looks over at Pat. The championship glow is still emanating from both of them, but it's no longer blinding. It's good light in which to look at Pat and assess. . . .

Does Michelle want to be like Pat? Does she want to make herself go cold and hard inside when she needs to, or is the cost too steep? Can she have children and sweep them along with her, the way Pat does with Tyler, showering him with love and attention on airplanes and bus rides, taking him and his nanny on road trips whenever he can go . . . then steeling herself and walking out the door alone when he can't? Can Michelle dress like the First Lady, give goose-bump-raising speeches, spearhead $7 million United Way fund drives, be competent in

everything—can she be, does she

want to be, the woman who's trying to do it all and pulling it off, as Pat is?

They climb out of the car, and Michelle stares across the hayfields and the tobacco barns and the silence. She gazes at the old homestead where Pat grew up, no girls her age within five miles. She sees the hayloft behind the house, blown off its 10-foot cinder-block legs by a tornado. It's where Pat climbed a ladder nearly every evening when chores were done and played two-on-two basketball under a low tin roof and two floodlights, on a tongue-and-groove pine floor surrounded by bales of hay, with three older brothers, two of whom would go on to play college sports on scholarship.

Michelle sees Pat's mother limp toward her on ankles worn to the bone by all the years of stocking shelves on a cement floor in the family grocery store, all the years of tucking her foot beneath the old 10-gallon milk cans, hoisting them off the ground and into the coolers with a thrust of her leg. All the years of milking cows before sunrise, picking butter beans all day in summer, laying down linoleum floors on the houses her husband was building to sell, never resting from the moment she woke till the moment she dropped into bed.

Michelle sees the three farms that Pat's father ran along with the feed store and the grocery store and the hardware store and the tobacco warehouse and the beauty salon, all while he was a school-board member and the county water commissioner. She sees the field where he once disked all night, then hitched up the mules and began planting corn until his head jerked and he saw that his rows were running together. She sees the white-haired man coming home from his tractor, on which he still spends 10 hours a day after two knee replacements, prostate surgery, two mini-strokes and quintuple-bypass surgery. She sees all the command and authority leak out of her coach as Tall Man draws near. . . .

Deference . . .

Pat? In a funny way, it's what Michelle needs to see: Pat's vulnerable. Pat's a regular person. Michelle does what Pat can't do. She walks up to Pat's dad and throws a hug around him.

She sees the schools where Pat never missed a day, not one, from grades one through 12, because illnesses were like birthdays—her father didn't believe in them. She sees the high school to whose district Tall Man moved the family just so Pat could play basketball, because he never separated what a girl ought to be able to do from what a boy ought to. Michelle sits at the table where the family still gathers often because only Pat, of the five Head children, has moved on. She sees how bare-boned and basic the family's life is, and how silly a spin move can seem.

She gazes across the dirt and asphalt roads where Pat used to take the family car, killing the dashboard lights so her kid sister, Linda, couldn't see the needle nosing 95, and it begins to dawn on Michelle that the wind that has been at her own back for the last three years is really the wind that has been at Pat's back all of her life. And that maybe you don't have as much choice as you like to think—after you've lived that long and that close to a force that strong—about the kind of woman you would like to be. Maybe the wind just sends you flying.

But the significant moment in Pat's story isn't back there, in the past, or even in all those traumatic and giddy moments that she and her point guard shared. The story doesn't end with Michelle—it goes through her, and on to people that Pat will never know, because Michelle is now the carrier of a spore.

A year after she leaves Tennessee and a few months before she joins the Philadelphia Rage of the ABL, Michelle meets a 15-year-old girl named Amanda Spengler, who plays basketball at a high school a few miles from Allentown, where Michelle grew up. Michelle takes Amanda under her wing—plays ball with her, lifts weights with her, talks about life with her and tells her all about Pat.

"She makes you feel there's nothing to be afraid of in life," Michelle tells Amanda. "If you want something, you go after it as hard as you can, and you make no excuses."

She tells Amanda how much she misses that lady now, how much she misses that sense of mission all around her—the urgency of 12 young women trying to be the best they can, every day, every moment. Sometimes in practice Michelle pretends Pat has just walked in to watch her, and she practices harder and harder. She tells Amanda how she dreams of being a coach someday, maybe even Pat's assistant.

"Let's run," she says to Amanda one day, but she doesn't run alongside the girl. She just takes off, barely conscious that she has already joined the legions of Pat's former players all over America who are spreading the urgency, breathing into thousands of teenage girls a new relationship with Time. She's barely aware that she's part of a capillary action, like the one that men have had with boys for generations, whose power is too vast to measure. She just takes off, determined to run seven-minute miles for 45 minutes, and Amanda gasps, running farther and harder than she ever dreamed she could, just trying to keep Michelle in sight.

A few weeks later Amanda goes to a high school track with a watch. We're talking about one girl now, remember, but we're

not. We're talking about a wave. It's midday in the dead of summer. Amanda starts running and realizes after three laps that she has almost nothing left, and there's only one way to come close to Michelle's seven-minute mile. Her face turns scarlet, her body boils, and her stomach turns; Nature screams at her to stop. Instead, she sprints. She sprints the entire last lap.

The watch says 7:05 as she crosses the line. Amanda can't believe she ran that fast, and she laughs as she reels and vomits near the flagpole. She laughs.