Growing up in a London village

June 17, 2016

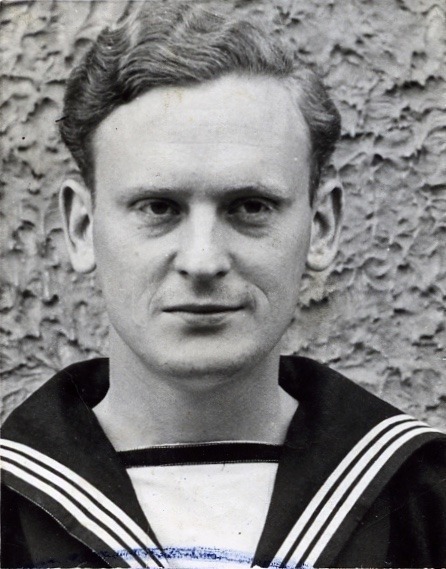

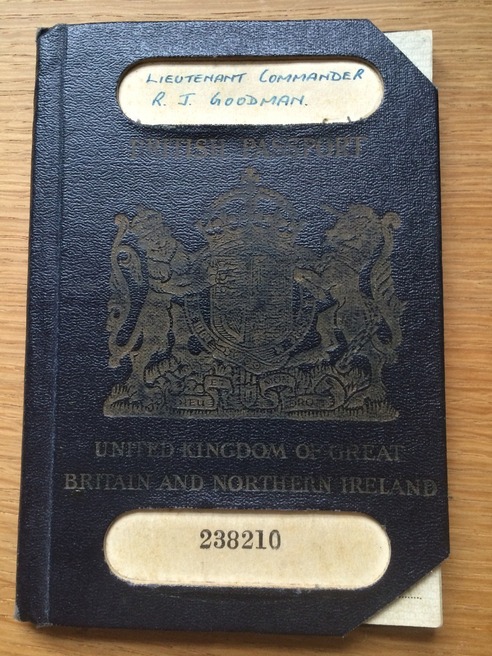

I was born and christened Raymond John Goodman in Highgate, London, on 26 October 1916. My mother Helena (known as Marion) Taylor Goodman was delivered of me in her father’s house in Chester Road, then took rooms in St John’s Wood where my brother David was born in March 1918, followed by Geoffrey in August 1919. My father, Joaquin (Joakey) Sedgewick Goodman had volunteered soon after the outbreak of World War I for the Middlesex Artists Rifles Regiment. He survived four years of trench warfare without a scratch, apart from a touch of mustard gas, and stayed in the army for a year after the armistice. When he returned from France they rented a large Victorian house at number 7 Dartmouth Park Road. Between the wars he made his living in commercial art, working for and later founding his own agency representing graphic artists and illustrators.

In 1925, with the help of Grandpa Taylor, our parents bought one of the newly finished houses in Makepeace Avenue on Holly Lodge, a garden suburb created from part of the Burdett-Coutts estate. The house had four bedrooms. As the eldest I was privileged to have a small front bedroom to myself; its main window looked over London and a window on the west side gave a limited view of Hampstead Heath. David and Geoff shared one of the other bedrooms, which left a room for our parents and another occupied for some years by a lodger.

As soon as I was old enough I went to a little private school maintained by some ladies up the street. Then I and the others attended state primary (or in US terms, public elementary) school on Burghley Road, about half a mile down York Rise and over the North London Railway tracks. After we moved to Holly Lodge that meant a walk over a mile each way. Since we returned home for lunch, we must have walked a total of four or five miles every school day. To relieve the tedium of the walk, we sometimes played marbles in the gutter on the way home.

When the family moved to Holly Lodge all three of us joined a troop of Wolf Cubs that had the use of an old stable in the grounds of the vicarage of St Anne’s Church, at the foot of West Hill. It was the start of a long career in the Boy Scouts. We went camping two or three times a year, learning to rough it in weather that memory tells was often cold and wet, and mastered the art of cooking over a log fire. We learned other skills such as life-saving, and some less obviously useful, such as how to fend off a mad dog with a scout pole.

In 1925, with the help of Grandpa Taylor, our parents bought one of the newly finished houses in Makepeace Avenue on Holly Lodge, a garden suburb created from part of the Burdett-Coutts estate. The house had four bedrooms. As the eldest I was privileged to have a small front bedroom to myself; its main window looked over London and a window on the west side gave a limited view of Hampstead Heath. David and Geoff shared one of the other bedrooms, which left a room for our parents and another occupied for some years by a lodger.

As soon as I was old enough I went to a little private school maintained by some ladies up the street. Then I and the others attended state primary (or in US terms, public elementary) school on Burghley Road, about half a mile down York Rise and over the North London Railway tracks. After we moved to Holly Lodge that meant a walk over a mile each way. Since we returned home for lunch, we must have walked a total of four or five miles every school day. To relieve the tedium of the walk, we sometimes played marbles in the gutter on the way home.

When the family moved to Holly Lodge all three of us joined a troop of Wolf Cubs that had the use of an old stable in the grounds of the vicarage of St Anne’s Church, at the foot of West Hill. It was the start of a long career in the Boy Scouts. We went camping two or three times a year, learning to rough it in weather that memory tells was often cold and wet, and mastered the art of cooking over a log fire. We learned other skills such as life-saving, and some less obviously useful, such as how to fend off a mad dog with a scout pole.