Excerpt from a piece about smoking written by Samuel Pilch, 1993.

They were called "loosies," two-cent cigarettes for kids who could only afford them one at a time. Shout "gimme a loosie!" through a dark opening and a gloved hand with exposed fingertips handed you one from between magazines, hanging comic books, and newspapers stacked for easy grab without breaking stride. And then there were other ways. A Benson and Hedges white-brick monolith stood on the corner down the street--our street. Many in the neighborhood worked the grinding machines that rolled long-thin sticks and placed virginal white filters on the end to attract more women to the smoke. In early afternoons we would scavenge the loading dock for survivors, cylindrical ingots that dodged the blemish of tread marks. Waving to friendly truckers as they pulled away, free smokes dangling from their lips and ours, hauling their fine-scented tobacco to thousands of candy stores and newsstands dotting New York's mean streets.

From the tenement stoop a kids' eye caught the changes, Old Country etchings of smells and sounds diffusing the new. Whispers telling of war in long forgotten neighborhoods and shtetls an ocean away finally ending, clusters standing in clouds of puffing smoke in shadows near flag-draped coffins. I remember cigarettes passed around in celebration of someone finding work, and the fear of a lost neighborhood when the crowd outside Kelly's Bar puffed and cajoled with theatrics of new ethnicity. Stoop elders mused about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory tragedy in a fire that took so many women and girl's lives. The power of smoke was yet a mystery, so they talked of disfiguring flames. How the fire reach them piled behind walls that should have had doors, door that were locked. In my world of incendiary, the few that abstained from the stick were oddballs, undeserving full membership in the block gang--street draftsmen patrolling borders, recording shifting edges and rims of the enemy; uniformed in pseudo-leather jackets and pegged pants, they hawked gangsterish phlegm down cracked sidewalks.

(...)

In sleepless early memories of my father, the white stick trailing smoke dominates, an appendage as recognizance as the features he was born with. His childhood is still a mystery to me. Never a snapshot of him running or climbing, or his mother's favorite first day at school. He was born an adult, went straight into the Army and picked up a smoking friend along the way. His silence at home, a brooding impenetrable wall of silence, moved me away to the noisy streets below--the cement playground of stickball games and stoopball games; the wonders of street corner turns and smells, and away from a tired old man, puffing and gazing at the nothingness on the kitchen wall.

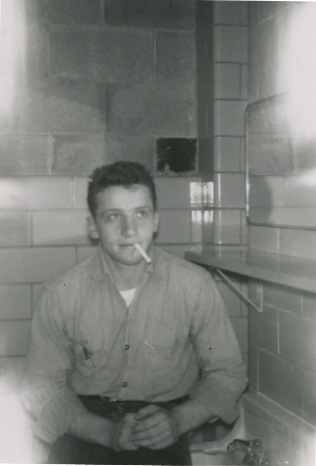

Today, mirrors reflect age and a smoking face that was once his. The same appendages ready to exorcise interlopers that interrupt a tight relationship: a pack of Nicotine Transdermal System patches staring menacingly from the shelf of my bookcase. And like a caring friend it tells me to give it a try. Just one patch. What have I got to lose? But like voices from tens-of-tousands of other mornings, I don't listen. The time is never right. So I reach hungrily for a smoke, and another, and another...prompting a search for beginnings--that shivering first moment when a dose of nicotine, clinging stealthily to swirling array of smoke came, unwelcome, for a short visit into this kid's lungs and stayed "the Marlboro Man" for the next 40 years.

One late summer evening smoking on the street corner, when the sun had long shut down but the tenement bricks convected daytime heat, I spotted a checkered cab moving up the street, slowly as a searching police car. And I just knew it was him--my father--too late for that rehearsed move into the shadows of the nearby hallway. I stood my ground, cupped the cigarette in my palm like the thugs in black-and-white movies working an apartment heist, then the voice, "I wish you didn't smoke son," in that slow, in control Ozzie Nelson drone, just loud enough for the street crowd to hear. Didn't hide. Stood your ground like a man. He parked his cab and joined me in a smoke. The boy to man/man to boy search for common ground had peeked through the surface...