A Life in Writing

October 18, 2020

Alastair was constantly writing—movie scripts and essays, short stories and articles, and always a stream of letters and emails to the people he loved. He wrote to share his thoughts about a piece from the latest New York Review of Books or to describe the details of a perfect day in Kyoto. He wrote to work out big thoughts about evolution or the state of filmmaking, or when he wanted to alert his children to a particularly amusing episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. And he wrote about his life. Over the years, across dozens of literate, thoughtful, loving messages, he told his life story in his own words.

- Nick

On growing up in Ireland, from a 2013 Email:

Bernice and I have been watching all the Downton Abbey series and it does bring back memories of my childhood in Coollattin. My father Wallace was the agent, very similar to the minor character in the third series who was insulted by the new plans to modernize. The estate was owned by a Lord Tom Fitzwilliam in distant England and only Lady Olive—the rather sad wife of the once romantic Peter Fitzwilliam who had run away with President Kennedy’s oldest sister—lived in the large house with a compliment of servants.

Without a Lord at Coollattin everybody on the estate, including all the staff, the butler, cook, lady’s maids, game keepers, chauffeurs, builders, gardeners, etc, were employed by Wallace, as were the many shepherds, laborers, carpenters, foresters, and other workers who managed the estate. Once the estate had been 85,000 acres, now it was about 20,000 acres—still a vast, almost self-sufficient, enterprise.

The estate looked terrible when we moved in, yet quickly the fields were greener, the hedges clipped, the farm buildings renovated, the gates painted, the large flocks of sheep and herds of cattle healthier. Wallace was a fine farmer and manager, and quickly the men on the estate came to be proud of the estate once again. I can remember coming home from English boarding school and being thrilled at just how beautiful the estate and surrounding countryside was.

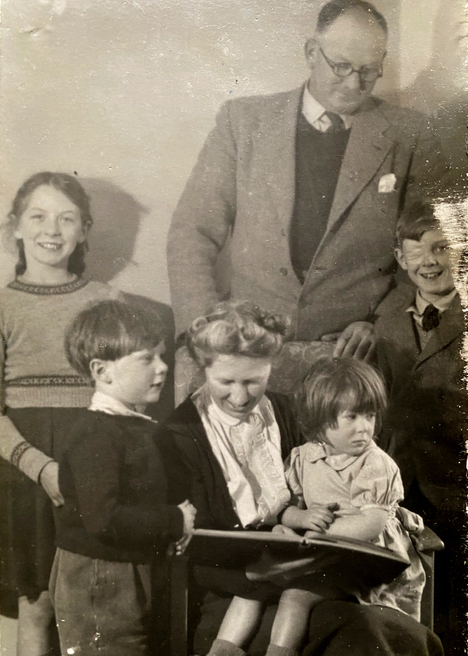

For us kids the estate was a magical and strange playground. Ginny and I in particular had a good time as Lady Olive was only too happy having us at the Big House, pleased to have young people to live through. Often Ginny and I, both still young teenagers, sat in the huge, gloomy dinning room, flanked by the butler and servers, eating a four-course dinner with three different wines while Lady Olive finished off a bottle of Scotch and talked of her youth as a flapper. Wallace disapproved but could hardly forbid us. In fact, I think Wallace disapproved of much of this world he ran—the shenanigans at the Big House, the influence of the Catholic Church on the poor, drunken Lady Olive, the fact that grown men were still willing to work in service, the poverty of all of Ireland at that time.

But unfair or not it was lovely for a child. Every day I would go for walks past Victorian walled kitchen gardens and stables, a glorious formal park with brilliant walks of rhododendrons and azaleas, a private salmon river, magnificent oak forests dating from the fourteenth century, a private golf course on which only David, I and a few locals used to play, a cricket field where once a year the house had a match with the village, abandoned houses, one with a ballroom, which Ginny and I explored, and everywhere overgrown signs of walls, drives, and abandoned gardens from eras when the estate had been even grander. And in the distance always lovely hills and fields. The estate had many horses including racing foals who would frolic and gallop in the field before our house; its own fox hunt; a weekly shoot with gamekeepers and beaters that in season attracted a dodgy raft of nostalgic refugees from England’s shrinking Empire, and every year our own point-to-point horse races. Like the TV series, we seemed to be forever living on the edge of history and ruin.

- Nick

On growing up in Ireland, from a 2013 Email:

Bernice and I have been watching all the Downton Abbey series and it does bring back memories of my childhood in Coollattin. My father Wallace was the agent, very similar to the minor character in the third series who was insulted by the new plans to modernize. The estate was owned by a Lord Tom Fitzwilliam in distant England and only Lady Olive—the rather sad wife of the once romantic Peter Fitzwilliam who had run away with President Kennedy’s oldest sister—lived in the large house with a compliment of servants.

Without a Lord at Coollattin everybody on the estate, including all the staff, the butler, cook, lady’s maids, game keepers, chauffeurs, builders, gardeners, etc, were employed by Wallace, as were the many shepherds, laborers, carpenters, foresters, and other workers who managed the estate. Once the estate had been 85,000 acres, now it was about 20,000 acres—still a vast, almost self-sufficient, enterprise.

The estate looked terrible when we moved in, yet quickly the fields were greener, the hedges clipped, the farm buildings renovated, the gates painted, the large flocks of sheep and herds of cattle healthier. Wallace was a fine farmer and manager, and quickly the men on the estate came to be proud of the estate once again. I can remember coming home from English boarding school and being thrilled at just how beautiful the estate and surrounding countryside was.

For us kids the estate was a magical and strange playground. Ginny and I in particular had a good time as Lady Olive was only too happy having us at the Big House, pleased to have young people to live through. Often Ginny and I, both still young teenagers, sat in the huge, gloomy dinning room, flanked by the butler and servers, eating a four-course dinner with three different wines while Lady Olive finished off a bottle of Scotch and talked of her youth as a flapper. Wallace disapproved but could hardly forbid us. In fact, I think Wallace disapproved of much of this world he ran—the shenanigans at the Big House, the influence of the Catholic Church on the poor, drunken Lady Olive, the fact that grown men were still willing to work in service, the poverty of all of Ireland at that time.

But unfair or not it was lovely for a child. Every day I would go for walks past Victorian walled kitchen gardens and stables, a glorious formal park with brilliant walks of rhododendrons and azaleas, a private salmon river, magnificent oak forests dating from the fourteenth century, a private golf course on which only David, I and a few locals used to play, a cricket field where once a year the house had a match with the village, abandoned houses, one with a ballroom, which Ginny and I explored, and everywhere overgrown signs of walls, drives, and abandoned gardens from eras when the estate had been even grander. And in the distance always lovely hills and fields. The estate had many horses including racing foals who would frolic and gallop in the field before our house; its own fox hunt; a weekly shoot with gamekeepers and beaters that in season attracted a dodgy raft of nostalgic refugees from England’s shrinking Empire, and every year our own point-to-point horse races. Like the TV series, we seemed to be forever living on the edge of history and ruin.