The tribute to Richard Elmore below was published in International Ed News on February 24, 2021. The original post can be accessed at:

https://internationalednews.com/2021/02/24/a-beginners-mind-remembering-richard-elmore/Use #RememberingRichardElmore to access and tag social media messages about and in honor of Richard in social media (Twitter, Facebook...).

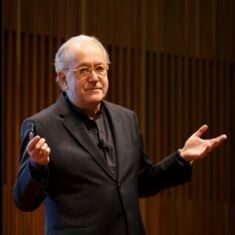

A Beginner’s Mind: Remembering Richard Elmore

Richard Elmore died peacefully and unexpectedly the night of February 9, 2021. I’ve found myself crying over the past couple weeks remembering Richard’s presence in my life as a mentor, a beloved teacher, and a dear friend. I get teary eyed each time I read over the outpouring of beautiful stories and messages shared in the online memorial site created by his family, and learning more about the powerful presence he had in the lives of so many - family, students, colleagues, and friends. Among the things treasured by those whose lives Richard touched are his sharp intellect, his generous heart, his contagious laughter, his profound respect for and belief in young people, and (especially in his later years) his growing irreverence for the schooling systems that constrain them.

The poet Naomi Shihab Nye once said “People don’t pass away./They die/ and then they stay.” There are many ways in which we can expect Richard to stay with us over decades to come.

Richard’s thinking has and will remain crucial as a reference to those seeking to understand how and under what conditions powerful learning can – and most often doesn’t – happen in schools, in school systems, and beyond. Some of Richard’s key contributions to the field that have stood, and will no doubt continue to stand the test of time include:

• Positioning the instructional core as the basic unit that our efforts as educators, teachers, school and system leaders should aim to transform fundamentally: “the problems of the system are the problems of the smallest unit”; “if it’s not in the instructional core, it’s not there”; “the real accountability is in the tasks students are asked to do”.

• Proposing a “backward-mapping” logic to examine, plan, and carry out education improvement work (starting from what you want to cause and moving gradually from the inside out to adapt the practices, systems and cultures surrounding it as change is underway);

• The notion that no amount of external pressure on schools will work in the absence of internal accountability (shared responsibility for improvement within the school) or reciprocal accountability (the responsibility of the system to invest the necessary resources and develop the necessary capacity of educators and leaders to produce the expected results) – “if you push an atomized, incoherent organization with an external accountability system, it will only become more incoherent.”

• His more recent exploration of ‘outlier’ groups and organizations that are nurturing and unleashing powerful learning among young people and children (NuVu, Beijing Academy in China, Redes de Tutoría in Mexico).

• His dire and sharp critique of the multiple ways in which schooling – the very institution intended to develop our young people’s ability and joy to learn – is getting in the way of powerful learning. (“A major lesson we have learned from attainment-driven models of schooling is that it is possible to disable human beings as learners by convincing them that they do not have the capability to manage their own learning”)

The list goes on, but I don’t intend here to cover the whole range of Richard’s intellectual and public legacy (a more detailed account of his outstanding public service and academic trajectory can be found in this post from the Harvard Graduate School of Education). I will instead share a more personal account of Richard as an example of a Beginner´s Mind, to illustrate how he stands out in the sea of internationally renowned education experts.

Richard knew a lot about schools, school reform, and education policy. And I mean A LOT. For many, students and colleagues alike, his mere presence was intimidating for this very reason. But much more prominent than what he knew was his disposition to learn: his openness to find surprise in the familiar and his willingness – almost eagerness – to put his own thinking to the test. I remember him telling me in one of our shared times in Mexico, with his loud, contagious laughter, how funny it was for him to find that people that organized a series of his talks in South America were shocked to find that he had learned a few new things in the ten previous years. His book I Used to Think… Now I Think is a beautiful collection of essays where prominent education thinkers are asked to describe some of the most important ways that their thinking has changed over the years. About the book, Richard remarked “It strikes me as ironic that in a field nominally devoted to the development of capacities to learn, there is so little evidence of what those who do the work have actually learned in their careers.”

Richard’s openness to finding surprise in the familiar is beautifully demonstrated in his habit of visiting classrooms one day every week. This habit, established after decades of studying education reform and policy, became an almost religious practice that opened Richard’s mind to the everyday realities of classroom practice and gave him an unmatched sensitivity and profound understanding of teaching and learning, and the many ways in which education policies with lofty intentions almost invariably miss the mark of affecting the instructional core in any substantive way.

It was Richard’s Beginner’s Mind that led him to accept my invitation to visit Mexico in 2010 to learn about tutoría (the pedagogical practice at the core of the Learning Community Project, also known as Redes de Tutoría). He endured an early morning flight and a ride of over 100 kilometers of bumpy, dusty roads to get to a remote rural community in the State of Zacatecas. Once there, he accepted the invitation of Maricruz, a 13-year-old girl from Santa Rosa to learn geometry with her support as a tutor. He was struck by her confidence and joy as a learner and a teacher, an experience that moved him (and all of us who had the privilege of being in Santa Rosa that day) to tears. It was Richard Beginner’s Mind that saw and named the Learning Community Project as a social movement, an insight that provoked in me what I can only describe as an intellectual awakening. It crystalized and integrated several ideas that had until then felt scattered and disorganized. This insight, a seemingly small side-comment in the vast extension of Richard’s thinking, is now foundational to my thinking and work on educational change.

I don’t know of another academic that is as openly willing – even eager – to prove himself wrong – as Richard was. You can see this in his writing and his public speaking. His book Restructuring in the Classroom with Penelope Peterson and Sarah McCarthey is an account of the disintegration of his faith in school restructuring as a strategy for instructional change. Here, he outlines that new school structures do not produce, as he initially believed, the changes in culture required to enhance the learning experience of children in classrooms. In his commentary paper “‘Getting to Scale’… It Seemed like a Good Idea at the Time” he reflects back on key flaws of his thinking 20 years earlier, articulated in his classic article “Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice.” In his last interview Richard talked about Instructional Rounds, a practice that he developed with colleagues at Harvard. He said it struck a chord with many school and district leaders, and that it helped them reconnect with their purpose, that it stimulated a lot of action and excitement. But – and here comes the punch line – he came to learn that “there was really not much relationship between satisfaction and impact.”

Richard died in the midst of a profound global crisis, in times where nothing less than the human project is at stake. In the world that we’re leaving behind, many academics have been revered for and built their identities around all they know. Richard’s conscious decision to maintain a Beginner’s Mind even at the pinnacle of his academic stardom shines as a bright light in a dark sea. I hope many of us will find in his example the courage to cultivate a Beginner’s Mind: to engage – as he invited us in his last podcast - in learning to do things we are fully incompetent to do; to be open to the awe of seeing the familiar in a new light; and to welcome with open arms the times when our dearest certainties are proven wrong. As the Buddhist tradition suggests, in a Beginner’s Mind lie the keys to a happier life and a healthier connection to others and the world – much needed features of the more conscious lives and the more humane world that we can build.

In his last years, in addition to taking on painting, Richard brought the attention of his Beginner’s Mind to the future of learning: the latest findings of the neuroscience of learning, the potential role of architectural design to represent and enable diverse models of learning; and the work of outliers in the learning world. His excitement about the future of learning however, grew in a way inversely proportional to his faith in schools and school systems. Richard grew increasingly skeptical about the prospect of schools and school systems becoming effective vehicles to protect and cultivate the extraordinary learning minds of our young people. He grew highly discouraged and impatient with how, to the contrary, compulsory schooling crushes the natural curiosity and joy to learn in children and youth. The last time I saw him in person, during a short visit to Boston, he told me he was working on a book of his latest thinking – one that, he confided to me with a playful smile, would likely upset many people.

Richard left a huge question for us to tackle: Will schools and school systems figure out a way to move away from schooling and cultivate powerful learning instead? His answer today would be a resounding ‘No’. I hope we’ll be able to prove him wrong on this one. I can picture him, with his Beginner’s Mind, laughing out loud with joy when we do.

#RememberingRichardElmore