Growing up in New York City 1944 - 1961

May 19, 2021

by Evelyn Sherr

Barry was born and grew up in New York City. His parents, Saul and Miriam, ran a mom-and-pop store in Greenwich Village that sold all sorts of hardware and housewares. Most of his ancestors had emigrated from Ukraine during the time of Russian programs on Jewish settlements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Sherr’s last name was originally multi-syllabic, but had been shortened to Sherr when the immigrants came through Ellis Island. Barry remembered an old relative who had served briefly in the Tsar’s army before emigrating.The man had personal stories about the pogroms.

Barry’s dad Saul was a tough, no nonsense guy. During World War II, his dad worked building Liberty Ships in New York shipyards. His dad said that one of his co-workers was a Nazi sympathizer. When an opportunity arose, Saul, working on a ship’s superstructure, managed to drop a heavy wrench on top of that worker’s head and 'accidently' killed him. When Barry was a young boy, a car came too close to him when he and his dad were starting to cross the street. Barry’s dad was incensed and dragged the car’s driver right out through the car's window to give him what for, which mightily impressed Barry. Another time, at the family dinner one night, Barry was giving his mom grief, which his dad didn’t appreciate. Saul threw a fork at Barry so hard it stuck into his stomach, which shut Barry up.

Barry also delighted in participating in getting the teacher’s goat in school.One teacher in particular was really dotty. One day all the students starting inching their desks up toward the front of the classroom when the teacher wasn’t looking.By the end of the period, all the desks were closely surrounding the teacher’s, which drove her nuts.

Both of Barry’s parents smoked, as did most people in the 1940’s and 50’s. Smoking was cool. Barry started sneaking cigarette butts and cigarettes from his folks as a pre-teenager, and kept up the habit until we had our kids in the early 1980’s.

While Barry was growing up, his family lived in a small apartment on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx and commuted to work at their store six days a week via subway. They hired a housekeeper to look after Barry in the afternoon after school and cook him dinner. Later Barry was a latch-key kid and said he liked to watch Perry Mason on TV to keep himself company. Another resident of the apartment building was the family of Penny Marshall, who went on to be a noted TV star. Penny’s mom ran a dance studio in the building, and Barry took dancing lessons there along with Penny. The Reiner family lived in a nearby apartment building; Barry remembers that Carl Reiner was a bit of an asshole to the kids in the neighborhood. A fond memory of that time was a local candy and soda shop, where Barry would get chocolate truffles and egg cream sodas. Barry also became a Boy Scout in an all Jewish unit for a brief time.

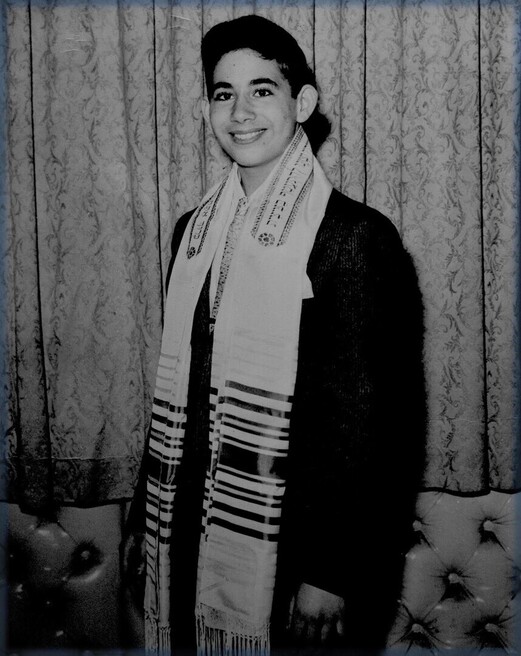

Although his parents weren’t very religious, his grandparents were, so when Barry was approaching his 13th birthday, he was enrolled in a program to get him ready for his Bar Mitzvah ceremony. He said the teacher was boring and the students cut up a lot. But he learned enough Hebrew to recite the Torah passage specific to his birthday. His parents had a gala celebration after his performance in the synagogue, with a feast for family and friends. One of the photos showed Saul sharing a cigar with his son, though Barry said his dad wouldn’t let him take a puff.

Barry took advantage of the great education of New York City schools, the Museum of Natural History, and youth programs like free youth symphonies held in Central Park. He went to DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, named for a 19th century New York City mayor and sixth governor of the state. Barry was involved in the drama club in the high school, and played a bit part in their production of The Importance of Being Ernest.

In the summer, his folks rented a house on Coney Island for a couple of months to escape the city heat. Barry loved to play in the ocean. While his father favored line fishing, Barry, who was enraptured by the adventures of Jacque Cousteau, made a do-it-yourself spear fishing gun, went diving off the local pier, and caught more fish than his dad did. Barry said those summer experiences and Cousteau gave him a keen interest in marine science.

When he was a teenager, Barry got a job working in the kitchen of an Italian restaurant near his parent’s store in Greenwich Village. He said the restaurant was owned by the New York mafia, and saw men he suspected were mafia often eating there. If a diner complained about his food, the waiter would take it to the kitchen, where the kitchen workers would often spit onto the corrected entrée before sending it back to the table.

Just before Barry went off to college, his family moved to the 13th floor of an apartment high rise in the Chelsea District of Manhattan, which was much closer to their store in the Village. Barry said he watched the World Trade Towers being constructed from the apartment window. (This same apartment building was used as a location for the 1999 movie 'Bringing out the Dead', which our son Aaron recognized from family visits to NYC when he saw the film).

Barry’s dad Saul was a tough, no nonsense guy. During World War II, his dad worked building Liberty Ships in New York shipyards. His dad said that one of his co-workers was a Nazi sympathizer. When an opportunity arose, Saul, working on a ship’s superstructure, managed to drop a heavy wrench on top of that worker’s head and 'accidently' killed him. When Barry was a young boy, a car came too close to him when he and his dad were starting to cross the street. Barry’s dad was incensed and dragged the car’s driver right out through the car's window to give him what for, which mightily impressed Barry. Another time, at the family dinner one night, Barry was giving his mom grief, which his dad didn’t appreciate. Saul threw a fork at Barry so hard it stuck into his stomach, which shut Barry up.

Barry also delighted in participating in getting the teacher’s goat in school.One teacher in particular was really dotty. One day all the students starting inching their desks up toward the front of the classroom when the teacher wasn’t looking.By the end of the period, all the desks were closely surrounding the teacher’s, which drove her nuts.

Both of Barry’s parents smoked, as did most people in the 1940’s and 50’s. Smoking was cool. Barry started sneaking cigarette butts and cigarettes from his folks as a pre-teenager, and kept up the habit until we had our kids in the early 1980’s.

While Barry was growing up, his family lived in a small apartment on the Grand Concourse in the Bronx and commuted to work at their store six days a week via subway. They hired a housekeeper to look after Barry in the afternoon after school and cook him dinner. Later Barry was a latch-key kid and said he liked to watch Perry Mason on TV to keep himself company. Another resident of the apartment building was the family of Penny Marshall, who went on to be a noted TV star. Penny’s mom ran a dance studio in the building, and Barry took dancing lessons there along with Penny. The Reiner family lived in a nearby apartment building; Barry remembers that Carl Reiner was a bit of an asshole to the kids in the neighborhood. A fond memory of that time was a local candy and soda shop, where Barry would get chocolate truffles and egg cream sodas. Barry also became a Boy Scout in an all Jewish unit for a brief time.

Although his parents weren’t very religious, his grandparents were, so when Barry was approaching his 13th birthday, he was enrolled in a program to get him ready for his Bar Mitzvah ceremony. He said the teacher was boring and the students cut up a lot. But he learned enough Hebrew to recite the Torah passage specific to his birthday. His parents had a gala celebration after his performance in the synagogue, with a feast for family and friends. One of the photos showed Saul sharing a cigar with his son, though Barry said his dad wouldn’t let him take a puff.

Barry took advantage of the great education of New York City schools, the Museum of Natural History, and youth programs like free youth symphonies held in Central Park. He went to DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx, named for a 19th century New York City mayor and sixth governor of the state. Barry was involved in the drama club in the high school, and played a bit part in their production of The Importance of Being Ernest.

In the summer, his folks rented a house on Coney Island for a couple of months to escape the city heat. Barry loved to play in the ocean. While his father favored line fishing, Barry, who was enraptured by the adventures of Jacque Cousteau, made a do-it-yourself spear fishing gun, went diving off the local pier, and caught more fish than his dad did. Barry said those summer experiences and Cousteau gave him a keen interest in marine science.

When he was a teenager, Barry got a job working in the kitchen of an Italian restaurant near his parent’s store in Greenwich Village. He said the restaurant was owned by the New York mafia, and saw men he suspected were mafia often eating there. If a diner complained about his food, the waiter would take it to the kitchen, where the kitchen workers would often spit onto the corrected entrée before sending it back to the table.

Just before Barry went off to college, his family moved to the 13th floor of an apartment high rise in the Chelsea District of Manhattan, which was much closer to their store in the Village. Barry said he watched the World Trade Towers being constructed from the apartment window. (This same apartment building was used as a location for the 1999 movie 'Bringing out the Dead', which our son Aaron recognized from family visits to NYC when he saw the film).